Calling something 'AI-crafted' is an oxymoron

In response to a backlash against artificially-generated content, the word 'craft' becomes a cynical defence.

By Ane Cornelia Pade

When McDonalds Netherlands launched a fully AI-generated Christmas commercial in December last year, outrage naturally followed. Many were quick to voice their concern that it was a sure sign that cinematographers, lighting and set designers would soon be a thing of the past. In response to the backlash, the production company behind the ad, The Sweetshop, released a statement describing the commercial as a ‘high-craft production’; a cinematic meeting between ‘craft and technology’.

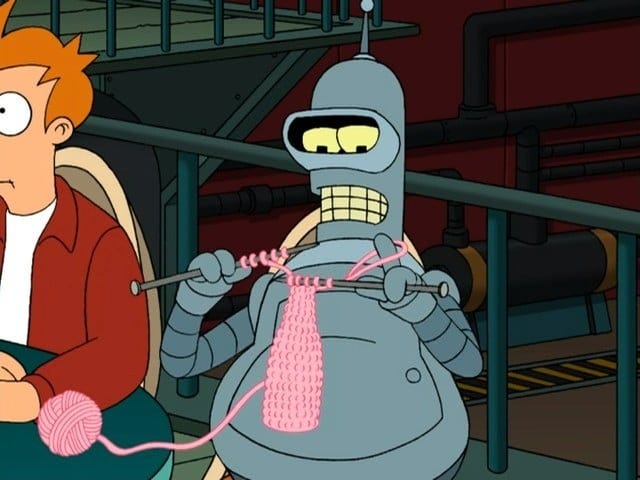

The crucial word in this deflection is craft. While the AI wave threatens to turn us all into doom-scrolling disciples of the algorithm, knitting, pottery, crocheting, and embroidery are quickly becoming more and more popular. Google searches for embroidery and crochet are up 18% from January last year, far exceeding the DIY craze of the pandemic.

So, the AI agency’s use of the word here is potent, signalling a clear attempt to inject the discourse around artificial intelligence and its depletion of human creativity with an association to art and handmade, tactile objects. The discursive grafting of AI onto craft is, at its best, a lazy attempt at giving it more value and, at its worst, indicative of the steady push to make the alien seem familiar by AI companies.

What The Sweetshop suggests is that, if there is human involvement, it can be labelled craft. This is, of course, not the case. Many flesh-and-blood humans are involved in industrial production, manning machines and filling out spreadsheets, but that does not make either the process or the result craft. Scholarship can help us tell the difference. The English philosopher Michael Oakeshott provides useful definitions of practical and theoretical knowledge in his collection Rationalism in Politics and Other Essays (1962). To Oakeshott, technical knowledge is that which follows rules, principles, and directions. It is knowledge that can be learned from a book or from an online course. Practical knowledge, on the other hand, cannot be taught but only imparted. It exists only in practice, and the only way to learn it is through continuous contact with the craft. In other words, practical knowledge requires apprenticeship and hands-on experience; technical knowledge does not. Oakeshott helps us keep in sight what does and does not belong under the heading of craft, keeping us critical of oxymorons like The Sweetshop’s ‘AI-crafted’.